The Legend of Ra and Isis

(Corpus of Turin Papyri)

Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis

Budge was born in Bodmin, Cornwall on 27 July 1857. Budge was an English

Egyptologist, Orientalist, and philologist who, for many years, was the keeper

of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities for the British Museum. A prolific writer,

he published numerous works on the ancient Near East. He died in London on 23

November 1934.

Budge attended Cambridge University from 1878-1883 and studied Semitic

languages, including Hebrew, Syriac, Ethiopic, Arabic and Assyrian. In 1883,

Budge joined the staff of the British Museum in the Department of Egyptian and

Assyrian Antiquities. He was initially appointed to the Assyrian section but

soon transferred to the Egyptian section, where he began to study the ancient

Egyptian language. Budge became Assistant Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian

Antiquities in 1891, and then was appointed Keeper in 1894, a position which he

held until 1924, specializing in Egyptology.

During his years in the British Museum, Budge established ties with local

antiquities dealers in Egypt and Iraq so that the Museum would be able to obtain

antiquities from them without the uncertainty and cost of excavating. Budge

undertook many missions to Egypt and Iraq and obtained enormous collections of

cuneiform tablets, Syriac, Coptic and Greek manuscripts, as well as significant

collections of hieroglyphic papyri. His most famous acquisitions were the

beautiful Papyrus of Ani (Book of the Dead), a copy of Aristotle's lost

Constitution of Athens, and the Tell al-Amarna tablets. His prolific

acquisitions gave the British Museum the best collection of Ancient Near East

tablets and Papyri in the world.

Budge was a prolific author, and

he is especially remembered today for his works on Egyptian religion and his

hieroglyphic primers. Budge's works were widely read by the educated public and

among those seeking comparative ethnological data, including

Sir James Frazer, who

incorporated some of Budge's ideas on Osiris into his monumental work entitled

The Golden Bough. Budge's works on Egyptian religion have remained

consistently in print since they entered the public domain.

Budge was knighted in 1920 for his distinguished contributions to Egyptology and

the British Museum. He retired from the British Museum in 1924, and lived on

until 1934, continuing to publish many additional books.

The following myth is taken from

ancient Egyptian Texts that were translated by

and published in his book entitled: Legends of the Gods

(London, 1912).

The Legend of Ra and Isis

(Corpus of Turin Papyri)

The original text of this very interesting legend is written in the

hieratic character on a papyrus preserved at Turin, and was published

by Pleyte and Rossi in their Corpus of Turin Papyri. French and

German translations of it were published by Lefebure, and

Wiedemann respectively, and summaries of its contents were given

by Erman and Maspero. A transcript of the hieratic text

into hieroglyphics, with transliteration and translation, was published by me in

1895.

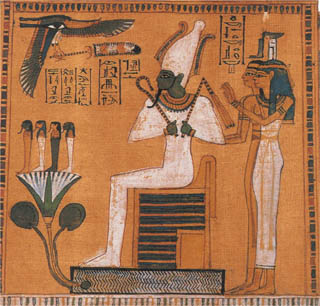

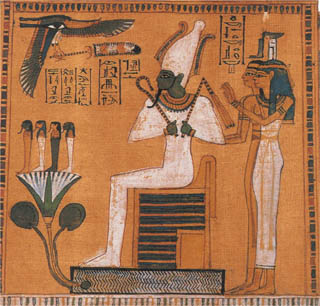

It has already been seen that the god Ra, when retiring from the

government of this world, took steps through Thoth to supply mankind

with words of power and spells with which to protect themselves against

the bites of serpents and other noxious reptiles. The legend of the

Destruction of Mankind affords no explanation of this remarkable fact,

but when we read the following legend of Ra and Isis we understand why

Ra, though king of the gods, was afraid of the reptiles which lived in

the kingdom of Keb. The legend, or "Chapter of the Divine God," begins

by enumerating the mighty attributes of Ra as the creator of the

universe, and describes the god of "many names" as unknowable, even by

the gods. At this time Isis lived in the form of a woman who possessed

the knowledge of spells and incantations, that is to say, she was

regarded much in the same way as modern African peoples regard their

"medicine-women," or "witch-women." She had used her spells on men,

and was tired of exercising her powers on them, and she craved the

opportunity of making herself mistress of gods and spirits as well as

of men. She meditated how she could make herself mistress both of

heaven and earth, and finally she decided that she could only obtain

the power she wanted if she possessed the knowledge of the secret name

of Ra, in which his very existence was bound up.

Ra guarded this name

most jealously, for he knew that if he revealed it to any being he

would henceforth be at that being's mercy. Isis saw that it was

impossible to make Ra declare his name to her by ordinary methods, and

she therefore thought out the following plan. It was well known in

Egypt and the Sudan at a very early period that if a magician obtained

some portion of a person's body, e.g., a hair, a paring of a nail, a

fragment of skin, or a portion of some efflux from the body, spells

could be used upon them which would have the effect of causing grievous

harm to that person. Isis noted that Ra had become old and feeble, and

that as he went about he dribbled at the mouth, and that his saliva

fell upon the ground. Watching her opportunity she caught some of the

saliva of Ra and mixing it with dust, she moulded it into the form of

a large serpent, with poison-fangs, and having uttered her spells over

it, she left the serpent lying on the path, by which Ra travelled day

by day as he went about inspecting Egypt, so that it might strike at

him as he passed along. We may note in passing that the Banyoro in the

Sudan employ serpents in killing buffaloes at the present day. They

catch a puff-adder in a noose, and then nail it alive by the tip of its

tail to the round in the middle of a buffalo track, so that when an

animal passes the reptile may strike at it. Presently a buffalo comes

along, does what it is expected to do, and then the puff-adder strikes

at it, injects its poison, and the animal dies soon after. As many as

ten buffaloes have been killed in a day by one puff-adder. The body of

the first buffalo is not eaten, for it is regarded as poisoned meat,

but all the others are used as food.

Soon after Isis had placed the serpent on the Path, Ra passed by, and

the reptile bit him, thus injecting poison into his body. Its effect

was terrible, and Ra cried out in agony. His jaws chattered, his lips

trembled, and he became speechless for a time; never before had be

suffered such pain. The gods hearing his cry rushed to him, and when

he could speak he told them that he had been bitten by a deadly

serpent. In spite of all the words of power which were known to him,

and his secret name which had been hidden in his body at his birth, a

serpent had bitten him, and he was being consumed with a fiery pain.

He then commanded that all the gods who had any knowledge of magical

spells should come to him, and when they came, Isis, the great lady of

spells, the destroyer of diseases, and the revivifier of the dead, came

with them. Turning to Ra she said, "What hath happened, O divine

Father?" and in answer the god told her that a serpent had bitten him,

that he was hotter than fire and colder than water, that his limbs

quaked, and that he was losing the power of sight. Then Isis said to

him with guile, "Divine Father, tell me thy name, for he who uttereth

his own name shall live." Thereupon Ra proceeded to enumerate the

various things that he had done, and to describe his creative acts, and

ended his speech to Isis by saying, that he was Khepera in the morning,

Ra at noon, and Temu in the evening. Apparently he thought that the

naming of these three great names would satisfy Isis, and that she

would immediately pronounce a word of power and stop the pain in his

body, which, during his speech, had become more acute. Isis, however,

was not deceived, and she knew well that Ra had not declared to her his

hidden name; this she told him, and she begged him once again to tell

her his name. For a time the god refused to utter the name, but as the

pain in his body became more violent, and the poison passed through his

veins like fire, he said, "Isis shall search in me, and my name shall

pass from my body into hers." At that moment Ra removed himself from

the sight of the gods in his Boat, and the Throne in the Boat of

Millions of Years had no occupant. The great name of Ra was, it seems,

hidden in his heart, and Isis, having some doubt as to whether Ra would

keep his word or not, agreed with Horus that Ra must be made to take an

oath to part with his two Eyes, that is, the Sun and the Moon. At

length Ra allowed his heart to be taken from his body, and his great

and secret name, whereby he lived, passed into the possession of Isis.

Ra thus became to all intents and purposes a dead god. Then Isis,

strong in the power of her spells, said: "Flow, poison, come out of Ra.

Eye of Horus, come out of Ra, and shine outside his mouth. It is I,

Isis, who work, and I have made the poison to fall on the ground.

Verily the name of the great god is taken from him, Ra shall live and

the poison shall die; if the poison live Ra shall die."

This was the infallible spell which was to be used in cases of

poisoning, for it rendered the bite or sting of every venomous reptile

harmless. It drove the poison out of Ra, and since it was composed by

Isis after she obtained the knowledge of his secret name it was

irresistible. If the words were written on papyrus or linen over a

figure of Temu or Heru-hekenu, or Isis, or Horus, they became a mighty

charm. If the papyrus or linen were steeped in water and the water

drunk, the words were equally efficacious as a charm against snake-bites. To this day water in which the written words of a text from the

Kur'an have been dissolved, or water drunk from a bowl on the inside of

which religious texts have been written, is still regarded as a never

failing charm in Egypt and the Sudan. Thus we see that the modern

custom of drinking magical water was derived from the ancient

Egyptians, who believed that it conveyed into their bodies the actual

power of their gods.